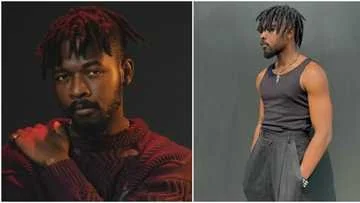

“The Church Shies Away from Love”: Johnny Drille Opens Up on His Musical Journey and Finding His Place Beyond Church Walls

Award-winning Afrobeats singer and songwriter, Johnny Drille, has opened up about his early struggles with finding acceptance in the church, despite beginning his musical journey there.

Speaking during a recent podcast appearance, the soulful singer — known for his heartfelt lyrics and soothing sound — revealed that although he once served as a music director in church, he often felt that his kind of music didn’t quite fit in.

“I didn’t feel like my music was predominantly in church. Every now and then, I get invited to churches to sing, which is kind of interesting,” he said.

Johnny Drille also shared how his transition from gospel to mainstream music drew criticism from some within the Christian community.

“I’ve gotten a bit of backlash from my Christian community every now and then when they invite me to churches. But at the end of the day, the music is positive. It speaks to good things that sometimes the church doesn’t want to talk about,” he explained.

He further addressed a topic many artists within the faith circle can relate to — the reluctance of churches to embrace songs about love and emotion.

“The church shies away from talking about love. A lot of times you go for Christian weddings and you hear Davido and Wizkid. What if the church decides that we want to start doing our own Christian love songs?” he questioned.

Reflecting on his humble beginnings, Johnny Drille said his experience as a choir director greatly influenced his growth as a musician, even though he wasn’t always in the spotlight.

“There’s a place for worship music, but there’s also music about so much more that the church could be singing about… I was a music director, but I never really sang in front of the church. I think it helped me become the musician I am today,” he added.

Opinion:

Johnny Drille’s reflection goes beyond music — it opens up a needed conversation about how the church relates to creativity and emotional expression. For too long, love songs have been seen as “secular,” when in truth, love is one of the most divine emotions.

Drille’s point strikes at the heart of modern Christianity’s artistic dilemma: should faith limit creativity, or should creativity amplify faith? His story shows that genuine art, even when it doesn’t sound “churchy,” can still inspire goodness, hope, and love — values at the very core of Christianity.

Perhaps it’s time the church stopped shying away from love songs and started embracing them — not as worldly distractions, but as divine expressions of human connection.

In Johnny Drille, we see a man whose art bridges the gap between the sacred and the soulful — reminding us that faith doesn’t silence creativity; it can actually refine it.